2020 was my fifth year of having Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and it was the year the world got COVID19.

In the Australian CFS community, the pandemic actually brought several benefits. For example, access to telehealth services, more money for those struggling to get by on the lowest rates of social security, potential insight into and empathy for our condition due to it’s similarities to being in lockdown, and the sad incidence of long-haul covid creating hope for more research into post-viral fatigue syndrome.

In Tasmania, lockdown happened between March and June. Many times I found myself rolling my eyes at the widespread angst, as unlike CFS, the lockdown was temporary, and people were still able to leave the house to exercise. But I do know it had a significant effect on the health of many people, particularly those with less housing security, in situations of domestic violence, and more susceptible to mental illness. And I would’ve responded the same had it happened pre-CFS. Still, it was a society-wide event. Many of the articles I read, about dealing with the mental health aspects of lockdown, would have made me feel much less alone 5 years ago, when I had the rug pulled out under my own feet, and vast amounts of time opened up without the ability to distract myself from loneliness, boredom, loss of control, fear, or ruminating on past regrets. It really is time to spare a thought for those of us who are enduring ongoing isolation and uncertainty, financial stress, and houseboundness, since long before and for long after 2020.

(Nb. I am fortunate to be in Australia, where the infection and death rates from covid19 have been relatively low due to effective containment of spread, and luck).

Later, when Victoria experienced their second wave, the lockdown protests made me think how with ME/CFS we are forced to be both our own strict governments (“dictator Dans”) and disgruntled citizens at the same time. To manage CFS well, you need to “lock yourself down”, long before you are noticeably tired, to hopefully prevent worsening of symptoms. It’s boring, frustrating, economically damaging, and it’s hard to see the point when you’re having a nice time and your glands are only a little bit sore. But prevention is better than cure, and seeing there is no cure for CFS, prevention is better than plunging oneself into weeks, months, or years of dismal post-exertional malaise, and lockdown enforced by acute, miserable sickness, rather than by sensible pacing measures. If only I was better at being my own police!

Back in March, covid did cause me a little extra stress, but on the whole, my life didn’t change much. I might've even felt a little smug. This is what I wrote on facebook:

“Personally feeling lucky. Even though my income is small, it’s guaranteed (for now), and I live within my means. My big disruption happened in 2016. I’ve had 4 years of practice of relative social isolation, and have no major plans for the rest of the year. I already bulk buy to minimize trips to the shops and have a stash of frozen chicken soup. Of course, I’m concerned about the impacts on the rest of society, I’m a bit stressed about our household response with a couple of people having differing opinions, I’m worried about the library closing and I’ll miss seeing my friends, but overall my life has not changed much “.

2020 had actually started off pretty well with my personal health. I was able to do quite a lot last summer, compared to the last few years. I went to see the waratahs at Mt Field with friends. Another friend helped me to go camping on Maria Island. I was doing stronger poses in yoga and hoping to build some core strength. I went on an eco-dyeing camp on the Tasman Peninsular and camping for a week at Fortescue bay. I was driving myself to appointments, the library, the tip shop, and social events. I was doing all my own food shopping, and even going for slow walks of up to 1km, which I actually put shoes on for. It was still very little compared to my previous life and very carefully managed and assisted, but it was much more ability than I find myself with at the end of the year.

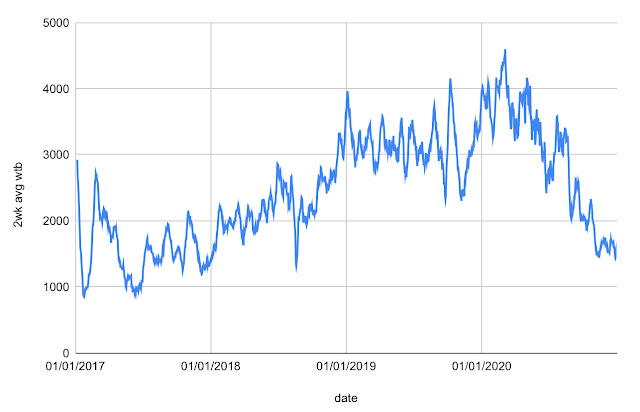

Starting about May, things began to deteriorate. Initially, it was only a gradual slide, and only really obvious in retrospect. I didn't really acknowledge it until September. But by November I tumbled down below the miserable line and became pretty much housebound again. I don’t know why my health went down the toilet again, and I spend too long making vague speculations. I can only wish that I had realized, and begun pacing more aggressively much sooner, and perhaps that might have helped. I had to relearn how to ask for help, negotiating the awkwardness and complexities of that, and surrender independence and control. At the moment I can still cook for myself, but I can’t do my own shopping, laundry, cleaning, gentle gardening, or go to the library. I had to cancel visiting my sicker, bed-bound friend. I haven’t been able to go sit in the bush, not even out the back of my house, as the hill is too steep.

In some ways, psychologically it hasn’t been as bad as my first year of illness. I have done this before and survived. I know about pacing better. I have better mental coping strategies. My previous life of climbing mountains, sea kayaking and body surfing is more distant. But it is still deeply, deeply disappointing. Now my hope of ever recovering is a lot less realistic than it was five years ago. I still miss what I could do in my previous life, and now I also miss what I could do a few months ago. Going to the mountain to sit amongst the trees. Going downstairs to the garden to pick fruit and vegetables. Independence. Having hope, that my upwards trajectory would continue, just because it had the last two years. It’s true that you need a lot less physical ability to be happy than I previously thought. And that slowness can be a gift. But I don’t think it’s worth pretending that sickness and the inability to do anything but shuffle to the toilet, mumble and lie on the ground is anything but plain miserable. It’s also true that occasional, temporary illness, absence, or deprivation can stop you from taking things for granted, and make you appreciate them much more when they are returned. But I think I am well past that point by now!

The worst of my loss has been not being able to go sit in the bush or by the sea. Nature time always helps my mental health a lot. Although I tried to pretend to myself otherwise, my life is really diminished without it. One day I did feel well enough to try to go sit at the waterworks, after 6 weeks of being housebound, and while driving in, I found myself feeling pretty weird. I think because while it was not an option, I was trying to be equanimous about, and satisfied with my only outdoor time being the front yard. Which is a nice front yard, with roses and garden plants and sky and grass. But. No creeks. No wildness. No smell of forest soil. Fewer delights and surprises of nature. I had lied to myself to try to suppress the pain of missing it. And when I went back to the bush, I felt resistant to loving it again. I didn’t want to need it or love it. The feeling fell away after some time as I lay on the earth by a creek under the tree ferns, and a very cute mother duck and her ducklings came waddling by. Unfortunately, I was exhausted after the trip and haven’t tried again since. So I’m not sure, how I will manage to be okay with being confined to the front yard, while painfully missing the bush. Let’s just say that it is my first priority when, or if I have the energy again.

At some point, I realized what I was experiencing was grief. Regular, commonplace, every person, everywhere grief. Although having a chronic illness is a particular type of ambiguous grief, more analogous to a missing person, than the death of a loved one. You still ride the exhausting rollercoaster of hope and disappointment, fear, and relief. And it’s deeply personal. What does it mean to grieve for yourself, and your lost abilities? Previously I had not thought much about grief until a woman suggested me a book about it a few years ago. I have only just ordered it and begun to read slowly.

The first chapter talks about how grief needs to be shared. But I am still wondering how, in this culture that can verge on toxic positivity. Or within the ME/CFS facebook support group which can already seem like an endless litany of misery, of people even sicker than I. And what’s even the point of talking about how crap this situation is when there’s nothing anyone can do? It’s not like I’m an unjustly detained prisoner and people can fight for my release. Although friends and family can and did bring food and flowers. They helped in the garden, gardened, shopped, cleaned for me. Some donated to research appeals. Another let me stay in their nearby bush cabin for a week.

I tried to share just enough on facebook so people could know my reality, even when they only see me when I have enough energy to pretend to be healthy, not when I am bedbound and suffering from PEM. Maybe some people thought I was a whinger or didn’t want to hear the miserable news of my decline on top of all the other bad news in the world. But others continued to be thoughtful, generous, and kind.

I’m guessing that the topic of letting go might be covered later in the book. In August, when I was still in denial about my decline, I went on an electric bike ride for the first time in over four years. The wattles were in full bloom, it was lovely, and my housemate was very kind to make it possible for me, by driving me and my bike to the start of a bush track. But after that, I crashed, and soon after that, my decline became unignorable. I thought about my lovely, expensive e-bike mostly sitting under the house doing nothing since I built it in 2016. I had great resistance to selling it because what I really really want is to ride it and not have CFS! Many people in the CFS support group shared similar stories of having to let go of items that represented their own hopes and dreams. Snow skis, a drum kit, a pottery wheel, and toys collected for their imagined future children. Someone suggested I needed to keep the bike in order to give me hope to get better, at which I balked. As if feeling sick, miserable, dependent, and stuck at home is not incentive enough to do whatever I reasonably can to try to recover. Anyhow, I have since lent it to a lady in the community who has less severe CFS than me and has been pining for her pushbike. It seems like the best possible outcome, save a miraculous recovery. Although the next step of actually selling it still feels hard. The e-bike example may seem trivial compared to the bigger things I need to let go of, like the realistic possibility of having kids, a relationship, or a career. But the conscious severing of a dream is different from a slowly diminishing possibility.

Anyhow, that was the big picture stuff of 2020. On a small scale this year I continued to do my yoga and meditation almost every day, except the super sick ones. The pandemic meant I was able to get digital access to my favorite yoga teacher again, which has been lovely, although I can't physically keep up with her instructions. I maintained my sleep hygiene and fussed around with a diet tracking app, trying to get enough nutrients while not gaining too much weight from being inactive. (I also stopped weighing myself in denial, as I already restrict my diet, and more restrictive diet attempts in the past have been unsuccessful and made me very, very grumpy). I dealt with several other bodily injuries, even though I wasn’t exercising, but may have been sleeping wrong. (Or perhaps it was from over-stretching in yoga, or is a consequence of 5 years of weakening muscles). I spent far too much time on screens. I binge-watched a tv show for the first time in my life, in winter when I had no housemates for a few months. I hated the feeling of addiction and tried to go cold-turkey, but watched until the end anyway. I won’t do anything like that again, only non-stressful ABC tv from now on!

I also spent too much time mindlessly scrolling facebook, often being triggered into sadness by other people’s happy photos. Five years can feel like a long time when friends have had multiple relationships, overseas trips, degrees, career changes, and houses. Babies that have turned into five-year-olds, five-year-olds into ten-year-olds, ten-year-olds into fifteen-year-olds, and fifteen-year-olds that are now twenty. Besides sometimes pettily not “liking” their post, I didn’t express my sadness. I hesitate to label it envy, as I know their lives are not perfect and facebook presents a skewed picture. And that I am better off than many, many people in the world. Still, I wished was better at being happy for other people, rather than sad about missing out. That I was better at holding my attention on the things I have, and things that are beautiful, rather than what I can’t have, or what is miserable. While trying to not deny and bottle up legitimate sadness. I am still not sure how to balance both, but I believe it’s possible.

Overall I still liked being alive. Until late October I sat in the bush. I visited friends, played the piano, painted tiles to decorate our garden, and went to music nights at our local food co-op. And even after my crash I read many wonderful books from the library, had nice housemates, ate delicious food, and drank delicious (decaf) coffee every morning. I admired my pretty garden. Flowers were delightful. I lay on the earth. I rubbed the belly of my housemate's dog. I learned some bird calls. I did a gratitude practice every day. I even made this word cloud of several months of my daily 'three happy things', so that this blogpost is not entirely depressing.

And so, onwards into 2021. Of course, I have hopes and dreams, but unlike what a physiotherapist said to me this year, with this illness it is not okay, and actually unsafe to have “goals”. Unless your goals are to never push yourself. To police yourself better. To live with more grace within your limitations. To be better at being happy for others. To be better at asking for help and not feeling like a burden. To be better at letting go of hopes and dreams, and focusing on what you have and not what you lack. To figure out how to not close yourself off to loving beautiful things, even when you can’t have them and it hurts. To allow the grief. I still have much to learn. At the moment it's still a day-by-day thing. Which is ok. That’s what this life is sometimes.

Postscript.

To practice, here are some of the things I currently have, that not everyone has, that I am grateful for and do not take for granted. The ability to read and write. Mental health. All four limbs in working order. All five senses. The disability pension. Access to the library. A good, sunny house in a nice neighborhood, with a bush and mountain view that has not yet burned down in a bushfire. A country that is not at war and has so far handled the coronavirus pandemic pretty well. Supportive and able friends and family. No abusive relationships. Enough food, and the ability to digest many delicious things. Relative lack of pain.